My novel, The Blue Room, was announced this week in the Maine Writers and Publishers Alliance Newsletter, Ex Libris.

|

|---|

My novel, The Blue Room, was announced this week in the Maine Writers and Publishers Alliance Newsletter, Ex Libris.

|

|---|

I’m pleased to announce that my first novel, The Blue Room, is now available on Amazon.com in Kindle ($13.00) and Paperback ($17.00) formats. You may also order it directly from me by emailing moriahfree@gmail.com

Thank you to everyone who has supported and encouraged me in its writing. May Kathryn’s story of healing and transformation resonate with all who read it, especially those who face the daunting challenge of living with chronic pain, illness, and emotional trauma.

************

Excruciating pain on the left side of her body wakes Kathryn from her trance of loneliness, stress, and exhaustion. She has pushed her mind and body beyond their reasonable limits; now, she is paying for it. She has ignored her physical and emotional needs and brushed aside her sadness while compulsively caring for others.

Now her body is screaming, enough! Stop!

But no matter what she tries, the pain does not stop.

Unable to work, sleep, or escape from the suffering and desperate for relief, she goes to see Dr. White, a pain management specialist. Their year of therapy transforms her life. The setting for her metamorphosis is The Blue Room. In this imaginary inner sanctuary, she discovers how the past has molded and imprisoned her and how she can set herself free.

In the fall of 2023, I purchased a package of twenty-four tulip bulbs from White Flower Farm. I planted them in the mid-November chill of Mid Coast Maine, hoping they would grace my front yard with some cheerful color come spring. Tulips and daffodils, like every other perennial, are always a risk in our frigid northern climate. I lose several plants yearly, no matter how carefully I bed them down for the winter. As I planted the bulbs, I remember saying to myself and others, “If this doesn’t work out, that’s it; no more attempts at my advanced age to improve the garden.”

Spring comes late in Maine, and I expectantly examined the front garden for weeks in April before I noticed the tiniest of green shoots poking through the brown soil. The steadily growing leaves, coaxed on by days of drenching rain and the occasional few hours of sunshine, cheered me tremendously. Leaves but no stems, though. My experience with daffodils has been that after the first year of blooms, I usually get nothing but leaves in subsequent years, no flowers. I feared the tulips would go the way of the daffs. But no, gradually, hearty green stems with tightly sealed blossoms shot up from the parting leaves. I counted. All twenty-four bulbs had produced a bud. I was amazed and gratified. Now, all I had to do was wait until the sunshine coaxed the buds into bloom. Or so I thought.

This spring, my household hosted a family of four chipmunks on and under our patio. We, the cats, and the dog watched, mesmerized as they scampered around, under, and over the patio furniture with acorns stuffed in their cheeks. They dug a neat burrow at the edge of a flower bed and, we imagined, created a warren of tunnels beneath it with living, pantry, and sleeping quarters branching off the main thoroughfare. These fantasies tickled us. Mom, Dad, and the two kids settled into their new home, slithering in and out of it many times a minute. We were delighted with their antics and those of their cousins, the grey squirrels, who are also abundant this spring. Last year was a mast year (a boom season) for acorns, so squirrels and chipmunks multiplied exponentially. Our side garden was a rodent carnival.

Meanwhile, out front, I noticed, one by one, the unopened tulip blossoms disappear, and their green leaves torn and tattered. Oh no! It must be the chipmunks and squirrels! But they don’t eat all tulips, apparently, because my neighbor’s yard was a riot of red, orange, and yellow flowers, as were many other gardens in our community. My heart sank. After all that work, waiting, and hoping, these entertaining little creatures, without regard for human labor, had stolen my joy.

I gave myself a little talking to: “They’re just flowers, they’re ephemeral anyway. They weren’t that expensive, so the loss is no big deal. You told yourself if this didn’t work, you wouldn’t try again, so just let it go!” Nevertheless, I googled how to prevent squirrels from eating tulips and found a recommendation to try cayenne pepper. We had none in the house, so I sprinkled red pepper flakes around the base of each plant instead. Completely ineffective.

Having given up on a riot of color like my neighbor’s, I considered how I might redeem the situation. I know so little about flowers and gardening that I had no idea what might happen if I cut the few remaining tightly closed tulip flowers and put them in water indoors. Even this modest experiment was fraught with risk. One of our cats eats flowers, so I had to hide my vase with the unopened tulips in the bathroom. Talk about letting go of my dream of a pretty bed of tulips in the front garden! I was making do with a few tiny green buds on the bathroom vanity behind a closed door. But somehow, the joy was just as sweet when I opened the door to these delicate blooms one morning.

This experience, in all its silly simplicity, speaks to me of the wisdom of letting go. Because so much is beyond our control and everything is constantly changing, creating any plan, investing any effort, and expecting or hoping for any particular outcome are risky business. We do all three continually, of course; they come as naturally as breathing. However, the pervasive visceral tension we carry proves that we live in a constant state of risk—risk of loss, failure, or disappointment. Any time we wake up to this reality is a moment of potential change. Missing tulip blossoms can speak to us of the groundlessness of our existence. They may carry the gift-wrapped message of surrender. Opening a bathroom door to behold pale reflections of pink and white flowers can offer a lesson in revision and redemption.

And how closely married are delight and destructiveness – chipmunk and squirrel antics on one side of the coin and flower devastation on the other. Imagine the deliciousness of tulip petals to a squirrel’s palate! Consider my sober, reasonable resolution not to waste time and money planting tulips again. The whole funny, frustrating, messy situation can be profoundly instructive if I let go and let it be so.

We never know what exquisite new vista the portal of disappointment will offer us or what ultimate peace might issue from the surrender of letting go.

I frequently visit a long-term care facility near my home. My dog and I go once a week to offer pet therapy to the residents. We walk from room to room, greeting the patients who pet the dog, smile at his simple tricks, and feed him treats as a reward. Occasionally, I also serve as a hospice volunteer in this facility, watching with someone who is dying through the dark hours of the night. For one reason or another, I’ve spent a good deal of time visiting nursing homes in Maine and Massachusetts, and this facility, in my experience, is one of the best. From an outsider’s point of view, it is clean and well-managed, with a full complement of services and a clientele that seems satisfied with their care. The staff is friendly to my dog and me, speaks kindly to the patients and treats them with gentleness.

Still, even in this seemingly best-case scenario, there are sometimes heart-breaking and gut-wrenching situations. Recently, nearing the end of a morning visit with my dog, I approached a patient we know well, who loves the little pup and whose attention he welcomes. She was sitting in her wheelchair in the hallway outside her room, looking anxious. I asked her what was bothering her, and she said she had been waiting for a long time for someone to take her to the bathroom. The young social worker who had just left her side had gone in search of a nursing aide to assist her. “It’s so hard,” she said, “when one gets old and bladder control is not what it used to be, and you call and call, and no one comes. Things have gotten worse,” she said. “One waits longer and longer now.” I expressed my sympathy and felt frustration rising in my chest. I also noticed a high-pitched wailing coming from the room opposite hers.

Someone else was also in distress. The room had a barrier across the door with a large stop sign in the center, indicating that only authorized personnel could enter. These detachable and portable barriers became common at the height of Covid outbreaks. “Help! Please help!” came the weak plea from the bathroom inside the room, but I could not go in to see what the matter was. I surmised the resident, whom we also know well, had been sitting on the toilet for a long time and was in discomfort or pain. The social worker approached again and reported that a nurse would be along shortly, after she finished putting another patient in bed. Timidly, I pointed toward the Stop sign and asked if she knew someone else needed help. She looked daggers at me, I guessed, for interfering, so I said goodbye to our friend in the wheelchair and walked on, frustrated, sad, and embarrassed for all of us.

The next day, when talking about aging with a group of healthy women in their sixties and seventies, I told this story and commented that this sort of indignity may await us all. I believe this common occurrence in senior care facilities is not the fault of nurses or other staff, social workers, or families, I argued, but the result of an ageist society that does not value the lives of those who are no longer financially or physically productive. An uncomfortable silence, a few somber nods of recognition, and a change of subject followed my candid expression of opinion. Understandably, no one wanted to discuss toileting in nursing homes or dwell on the possibility of finding ourselves in similar situations down the aging road.

I wrote about the indignities of the senior healthcare system in an extended series on The Elderly and End-of-life Care in 2017 when I launched this blog. Things have not changed since then, and because of further staffing shortages, they have worsened in many ways.

This kind of indignity may await all of us. More and more of us are living into our nineties because of medical advances producing life-prolonging disease treatments and cures. The healthcare system is stretched beyond measure, caring for an ever-increasing percentage of seniors in our population. We take advantage of every possible means to prolong our lives. Covid has decimated the ranks of healthcare professionals, and the greed of insurance and drug companies complicates matters further. I frequently hear my contemporaries say that the system is broken. They can’t get direct face time with their primary care doctors, or appointments with specialists, or get their prescriptions promptly. Doctors and nurses are quitting in frustration or from burnout. In-home care is exorbitantly expensive, and the agencies that deploy homecare workers are limping along with a few staff members. Of course, the financially secure have it far better than low-income people. That goes without saying, but no matter how financially secure you are, your dignity will be in jeopardy if you can’t get someone to take you to the bathroom.

Or will it? In these recent posts, I’ve been encouraging us to think about practicing for The Big Let Go—death. I’ve been recommending we consider learning to let go in small ways in ordinary daily situations to be ready to let go in a big way at the end of our lives. Am I suggesting that we must let go of our dignity? No. I am proposing that we consider where our dignity truly resides.

Does our dignity depend on how others treat us, or is it reflected in and demonstrated by how we treat others? My friend waiting for assistance to go to the bathroom was calm, polite, and sad but not angry, even though she faced the indignity of potentially soiling herself while she waited. The other patient, pleading for assistance from her bathroom, said, “Please.” Can we learn to relinquish the external signs of dignity while holding on to our inner poise, beauty, and self-esteem? And how can we practice doing that today?

How do we respond when someone wounds our dignity in small or large ways? Can we still insist upon the outward recognition of everyone’s dignity while more highly valuing intrinsic worthiness, integrity, humility, and courage as the essence of our humanity?

We may not all end up in situations like the patient in the wheelchair waiting for assistance with toileting. We may be lucky enough to die suddenly or in the comfort of our homes, surrounded by those who love us and tend promptly and respectfully to all our needs. We may live an active and independent life, avoiding physical dependency on others to the end. But if we don’t practice letting go of external signs of respect while holding fast to inner dignity, we may lack the necessary interior resources to draw upon as we approach The Big Let Go.

If you want to accord with the Tao,

Just do your job, then let go.

—The Tao Te Ching, translated by Stephen Mitchell

I’m a planner, but I’m not naïve enough to think that meticulously planning something will make it turn out exactly how I want it to. Decades of experience have taught me that control is an illusion—a dear one. Still, planning is in my bones, and I might as well embrace it as part of who I am. Planning, like everything, has its shadow side and its bright side. The shadow side is about clinging—to outcomes. The bright side is about creativity, fruition, and letting go.

Giving myself fully and genuinely to a task or project without getting attached to the final product is one of my biggest challenges. How does one go all-in on something without being wedded to the result? I care; therefore, I plan. I do everything possible to ensure the desired outcome has its best chance.

I’m talking about passion—giving everything you’ve got, then offering your beloved creation to the world and letting go. Huge risk, right? Like nursing an injured baby seal that has beached itself. You painstakingly feed it, protect it, and watch it regain its strength, then set it free with absolutely no expectation that you will ever see it again or faith that it will survive beyond your sightline as it heads out into the deep. Or, like a parent raising a child, I imagine, since I have never raised one.

A friend of mine advocates “holding things lightly,” meaning, I think, that caring passionately and relinquishing control are both essential to being fully alive. It is possible to be committed to an outcome and hold it lightly, ready to let it go. Challenging but possible.

Scientists tell us we are hard-wired for planning. Research has shown that some areas of the brain, known as the default mode network, carry out this planning function. They

“become active when our attention is not occupied with a task. These systems function in the background of consciousness, envisaging futures compatible with our needs and desires and planning how those might be brought about….Human brains have evolved to do this automatically; planning for scarcity and other threats is important to ensure survival….Our background thinking is essential to operating in the world. It is sometimes the origin of our most creative images.” Why we are hard-wired to worry, and what we can do to calm down (theconversation.com)

So, we will plan no matter what, and sometimes planning, when unhooked from worry, can be a very creative and valuable form of flow state. If I am going to plan, I want to give it my very best effort. I want the idea and the plan for its execution to be as detailed as possible, take as many contingencies as conceivable into account, and be thoroughly tested, broadly vetted, and profoundly considered. I want to be wholly absorbed, plan passionately, launch my plan confidently and enthusiastically, and then let go of the outcome!

Why? Because no matter the outcome, whatever happens—success, disaster, or somewhere in between—is an opportunity for learning, growing, transforming, and embracing reality just as it is.

Sometimes, when I meditate, my mind is pulled toward a problem that captivates me or a situation that needs resolution. I try to turn away from the flow of thoughts and return focus to my breathing once, twice, three or more times. Finally, I will sigh and let my mind have its way, go with the flow. Sometimes, the most fitting solutions emerge from giving my default mode network free reign. I’ve learned, though, not to act on these plans immediately but to let them mull and mature for a while and to be willing to let go of them, to change my mind.

During my 71 years, life has required me to let go of hundreds of cherished outcomes for multiple carefully laid plans. It’s gotten easier as I’ve begun to notice a pattern of unexpected gains amid losses, of auspicious signs amid clouds of disappointment. Gradually, I’ve become more curious about than afraid of the unknown final outcome of life—my life.

This past week, the Christian Church celebrated Ash Wednesday, the day of the year when we look death straight in the eye and remember that we all came from dust and will ultimately return to it. “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” One of the ministers at the Episcopal Church in my town told me that some clergy are now reciting the words, “Remember that you are stardust, and to stardust you shall return,” when they imprint the sign of a cross in ashes on their members’ foreheads. The words point to our smallness and our greatness and are a sparkling reminder that we have always been and will always be part of the immense universe. How I cherish that outcome!

In the last post, I wrote about practicing for the ultimate let go at death by letting go regularly in daily life. The notion is that we get better at letting go the more we do it. Before further exploring the wisdom of letting go, I want to explore a phenomenon that often accompanies it—the experience of shutting or closing down.

Letting go implies some degree of attachment or clinging. Releasing our hold on something is frequently a viscerally painful experience. Relinquishing our illusion of control can seem almost impossible. We think we’ve done it, but our controlling behavior insidiously creeps back in. Letting go of cherished hopes and expectations brings feelings of loss, disappointment, and grief. Setting free those we love can feel like ripping our hearts out. Letting go can provoke anxiety and fear—a sense of lostness, vulnerability, and meaninglessness. All of these feelings, I suspect, are also common as we approach death. The supreme challenge in letting go is to stay open, receptive, and hopeful instead of closing or shutting down and donning the protective armor of fantasy, cynicism, or denial.

Let’s bring it closer to home with an example. You offer an idea to a group of your peers. It’s an idea born of years of experience and hours of careful thought about the problem you’re all trying to solve. Your group has struggled with this problem for a long time and made no progress. Your idea seems bold and a little far-fetched, perhaps intuitive rather than logical, but you can think of no other way. Not only does the group reject your suggestion without seriously considering it, but they ridicule you for offering such a risky proposal. They are sure you’re mistaken.

Okay, you think, just let it go. This suggestion is the best I have to offer; now, I must let go and let whatever happens happen. You relinquish control and wait, but not with a feeling of open anticipation and hopefulness. Instead, you shut down, you can’t stay open to the ideas of others, and you can’t entertain any new ones of your own. You may feel rejected and withdraw physically or emotionally. You close down—put on a defensive armor that blocks your participation in life’s miraculous, ever-changing flow.

Authentically staying open after genuinely letting go is one of the most elusive of human responses. Three orientations may promote this precious openness. They were suggested to me by the poet and philosopher David Whyte, the Buddhist nun Pema Chödrön, and the Christian saint Julian of Norwich. I can’t decide if these attitudes have a hierarchy of value, so I will offer them alphabetically by first name.

David Whyte. Recently, a friend told me about his book Consolations, first published in 2015 but which I had not encountered before a couple of weeks ago. It is a series of reflections on the meaning of various words. Oddly enough, his reflection on silence is the one that gives me a clue about how to stay open after letting go.

“Reality met on its own terms demands absolute presence, and absolute giving away…a rested giving in and giving up; another identity braver, more generous and more here than the one looking hungrily for the easy, unearned answer.” [Page 116]

“…braver, more generous, and more here.” The ability to remain bravely and generously present in the reality of each moment brings about the stance of openness. It is much easier, perhaps only ever possible, to welcome what is happening here and now.

Julian of Norwich. An anchoress in the Middle Ages, Julian famously wrote in her Revelations of Divine Love, “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.” The phrase expresses a generalized hope that everything will ultimately turn out not only okay but well and beautifully. Specific hope for a particular outcome may be doomed to disappointment, but general hope in the goodness of life and death enables one to stay open after letting go.

Pema Chödrön. One of Chödrön’s prevailing themes across all her writing is learning to be comfortable with the natural human condition of groundlessness—accepting and familiarizing oneself with uncertainty and feeling safe amid constant change. Buddhists call it impermanence, one of the Three Universal Truths of Buddhist philosophy—safety without control.

So, as I write and we think together about letting go without shutting down or closing up, can we draw on the wisdom of these three guides and remain open in the here and now, with a sense of cosmic hope and ultimate safety? Let our imagination peel back the layers of our chests and gently open our hearts to the miraculous mystery that letting go will reveal.

I’ve been using this phrase for some time now. When I drop it into conversation, as in, “I’m practicing for The Big Let Go,” I usually get a puzzled look from the one I’m talking to. When I explain what it means, I get a “You’ve got to be out of your mind!” look.

So, what is “The Big Let Go?” Well, it’s Death, of course—the most crucial moment of letting go in our lives. Death is when no more alternatives, options, arguments, or excuses exist. Procrastination is impossible; the hope of avoidance is patently hopeless, and you are entirely alone, whether or not a friend or loved one is sitting at the bedside holding your hand. It is the ultimate moment of giving in, surrendering, and trusting—letting go of control and our grip on life.

Some go out fighting, refusing to let go until death steals their last breath. That’s usually not a pretty or dignified exit, which is what we all want, whether we say so or not. How often have you heard someone say they hope they die peacefully in their sleep? And speaking of sleep, it’s a perfect opportunity for practicing letting go—or death, to put it bluntly.

What does it mean to practice something? The Oxford Dictionary defines practice as “repeated exercise in or performance of an activity or skill to acquire or maintain proficiency in it.” Synonyms are training, rehearsal, repetition, drill, and warm-up. Practice makes perfect, we say flippantly. Practice is mundane and often drudgery; perfection is sublime and unachievable. The child practices the piano faithfully to win an invitation to play at Carnegie Hall; you practice your golf swing to win the office tournament. I practice drawing to become an artist or throwing pots to become a potter. We practice silent restraint so that our angry words don’t hurt others, or we practice listening attentively and openly to understand one another.

Practice develops skills and changes habits. It can change your life, even set you free from addictions and compulsions. In a sense, we are what we practice—from the mundane (I brush and floss my teeth meticulously to have a healthy, attractive smile) to the sublime (I practice meditation daily to be in touch with my true self and reality.)

The notion that one might practice letting go throughout one’s life to be good at it when the time for death arrives is, for many, weird and morbid. It may be so for those who see death as a tragedy, a loss, something to be resisted and put off. But in all faith traditions and reports of near-death experiences, death is portrayed either as a moment of release, culmination, reward, or welcoming, or, conversely, of terror and punishment, depending on what one has practiced in life.

Buddhists are encouraged to think of death frequently to be ready for it and for what it can teach them about how to live before it arrives. Charnel Ground meditation involves imagining or observing the gradual dissolution and decay of the body to internalize the truth that all things are impermanent—everything changes and passes away.

Christian reflection on death focuses more on reward or punishment and is encouraged to put the fear of God, the ultimate Judge, into its adherents. According to theologians, Jesus died and rose again to save us from death and damnation.

But in general, and particularly at this time in history, we ignore death until it becomes unignorable, and then we lament it. So, how counter-cultural is the notion of practicing to do death well—gracefully, peacefully, with joy and dignity—instead of hanging on for or to dear life? Can one practice gently relinquishing, letting go, releasing, and opening to the unknown daily to prepare for The Big Let Go?

Pema Chodron, in her book How We Live, is How We Die, quotes a verse from a Tibetan Buddhist teacher, Dzigar Kongdrul Rinpoche,

“When the appearances of this life dissolve,

May I, with ease and great happiness,

Let go of all attachments to this life

As a son or daughter returning home.” (p.22)

I find this image of a child returning home enormously comforting. It conjures up memories of long day trips when I was young, perhaps to visit relatives or friends or the beach. Days full of play and food would end with a car ride homeward in the dark. We kids would fall asleep in the backseat, lulled by full stomachs, the hum of the car engine, and the rocking of the seats beneath us. Then, when we finally arrived home, we’d be carried inside, undressed, and put to bed in the safety and familiarity of our rooms. What ease and great (sleepy) happiness!

Or imagine the scene of the Prodigal Son in Jesus’ parable. The dirty, starving, ashamed son returns home to a father’s generous welcome, greeted with a feast, new clothes, and the warm embrace of forgiveness. What ease (relief) and great happiness!

Death may not resemble either of these images, but I believe it is a return to the source of all life. If death is a return to our source, it is impossible to do it without letting go of our attachments to this life—a tall order indeed. It involves letting go of our attachment to our youthful good looks, our health and strength, career and family successes, fame, financial security, mental acuity, friendships, loves, regrets, anger, fear, and failures. I could go on.

Since dropping these far-reaching and self-defining attachments is a momentous task, I believe it is worth practicing now for the challenge ahead of us. For some time, I have been trying to recognize small and large opportunities for letting go in my daily life—letting go of people, outcomes, feelings, memories, hopes, expectations, opinions, and judgments. When I encounter an opportunity for letting go, I try to notice what it feels like in my body, first to hold on and then to let go. Viscerally, the experience of holding on is tight and painful; letting go is a feeling of “ease and great happiness.”

Over the next few posts, I will explore some everyday experiences of letting go, keeping in mind that you, like I, may want to develop a skill that will stand us in good stead when The Big Let Go arrives. Will you reflect and practice with me?

Heedful of the 15-mile-an-hour speed limit, I drive carefully through the empty streets of my retirement community on an ordinary day. Suddenly, I see something extraordinary.

A Great Blue Heron presides regally on the left side of the road. Holy s_ _ t! I whisper to myself as I pull cautiously to a stop. The bird is immense, nearly as tall as I am. It looks at me intensely, slowly turning its small head atop its slender curved neck so that one eye can focus on my fire engine red car a mere twenty feet away. Its black legs equal nearly half its height. A pale blue-grey, aerodynamic cluster of chest feathers and folded wings perch atop them. The neck flows upward from this central mass and is crowned by a proportionally small head and a disproportionally long, pointed beak. The bird stares calmly; I stare, slack-jawed and awestruck. Moments pass, each of us immobile. Then, gracefully, the heron lifts one thin pole of a leg, revealing four equally skinny toes, three in front and one in back, bends its miniature knee backward, and steps over the low wooden barrier on the side of the road. It follows with the second leg and glides elegantly down the steep bank littered with fallen oak leaves, broken branches, and rotting tree trunks toward a shallow pond.

Wanting more, I push the gear shift into “park,” slide out of the car and grab my iPhone from my right back pocket. I walk quickly but fluidly—not to frighten the bird—to the side of the road and look down the bank. The heron has already reached the pond and is moving deliberately through the water on its stick legs. It is well camouflaged by autumn golds and browns—bare branches, yellowed leaves, and black water. Its body feathers blend with the trees, and its legs, neck, and pointed beak are almost indistinguishable from the willowy saplings around it. The Great Blue appears to be the forest gliding through itself.

The terrain is too steep and cluttered with woodland debris for me to descend on the same route as the bird, so I swing around to the right and take the familiar path to the pond, clicking pictures of the heron whenever it emerges into view through the underbrush. Click, click, click. (None of the shots are any good; it turns out later.)

Finally, he stands still at the edge of the pond. I do, too. I am entranced—all glowing eyes and beating heart. I don’t know how to take in such exquisite beauty, powerful fragility, and deep composure. The heron and I are alone together. From my perspective, I am the admirer, and he is the admired—there is no space in my mind to consider his perspective.

For several minutes, neither of us moves. Then I think, I have to tell someone! Quietly and slowly, I turn and walk back to my car, still idling by the side of the road, the driver’s door open. I slip my phone back into my pocket, drive the remaining minute to my front door, and burst in, “There’s a Great Blue Heron in the pond!”

Sarah Faith is impressed and immediately Googles “Great Blue Heron” on her iPad, reading aloud to me the information the search engine pulls up. It is a large bird with a wingspan of 5.5 to 6.6 feet and a height of 3.2 to 4.5 feet. It hunts alone but nests in colonies, usually in tall trees near water sources. It feeds mainly on fish but also eats other aquatic animals, insects, and rodents, and it can eat up to two pounds of fish per day.

In Native American tradition, it is associated with good luck and loyalty. In Christianity, it represents perseverance and patience. In Celtic tradition, it heralds renewal and calmness in challenging situations. It symbolizes the characteristics of balance, strength, clarity, and connectedness.

The facts, myths, and omens wash through my ears and into my brain. Google encourages me to consider my encounter with this bird a fortuitous event. But I’m only half paying attention, impatiently, to the information. I feel a powerful urge to return to the pond as quickly as possible to see if the heron is still there—to feast my eyes on this miracle again. But I don’t go alone. My entrenched sense of responsibility reminds me that my dog needs his afternoon walk, so I leash up the frisky little guy and take him with me, insisting, “No barking!” as we go.

It takes only a couple of minutes for us to reach the pond. Lo and behold, the heron is still there, standing stalk still in the same spot it was ten minutes before. Because it is camouflaged, the dog doesn’t see it, and it is too far away for him to pick up a scent, so while he sniffs the decaying leaves at our feet, I stand and gaze again. The heron is not fishing; it’s waiting. Motionless, we watch each other.

Moments pass, and I have another brilliant idea. I must share this experience with someone likely to appreciate its specialness as I do. I think of my neighbor on the street next to the pond, a woman who loves the forest and its creatures. You stay there, I silently tell the bird, I’ll be right back.

I knock on my neighbor’s door; sure enough, she’s interested in seeing a Great Blue. While she puts her coat on, the dog and I shuffle from foot to foot impatiently. When she emerges from her front door, and we walk toward the pond, we hear a faint drone in the distance. “Leaf blowers!” she exclaims, extremely annoyed. “They ruin this place. They drive me nuts!”

I try to be sympathetic, but I want her to focus on the beautiful bird I am sharing with her. However, the noise from the blowers has ruined it for her, and perhaps for the heron too, because he looks around anxiously after a few more moments and glides upstream toward the footbridge. My neighbor and I decide it’s time to move on and leave him in peace. She invites me to walk in the woods a little longer, and we take the dog for his afternoon stroll together, chatting quietly about the quotidian details of our lives: sleepless nights, failing health, and community news.

Later that afternoon, in a pause between activities, I recall the image of the Great Blue. I’m antsy and annoyed with myself. I sense I’ve missed a profound opportunity for communion and insight. I rehearse the compulsive behaviors that prevent me from being fully present in life: photographing experiences to preserve them, researching facts to understand, seeking to share soul-stirring occasions with others to pursue intimacy, and letting responsibilities deflect me from my heart’s call. Why could I not simply stand still and look, listen, and open myself? Why could I not be fully aware of the essence of the encounter? Might a veil have lifted? Might I have seen the truth?

The following morning, during meditation, I calm my agitation and recall the image of the Great Blue, as I first saw it, regal, by the side of the road. I breathe deeply and gaze long, feasting on the mental vision with my third eye, the eye of intuition. The bird, in all its majestic peacefulness, revisits me. This time, instead of analyzing it, I recognize it. I know it for who it is—an avatar. The divine source of everything, incarnate in the form of a Great Blue Heron, stands amid an ordinary day. Solitary yet inseparable from the world, it moves effortlessly through beauty, chaos, and debris, self-assured, serene, and unafraid.

In the last few weeks, I’ve repeatedly returned to my mental picture of the Great Blue Heron. Each time, I feel revisited by an inexpressible peace and humble confidence that the bird and I are kin. I am also an avatar, an incarnation, though partial and flawed, of the source of all goodness. Each time the vision of the Great Blue returns to me, I am certain of the indestructibility of this exquisite world, the love from which it is born, and my intrinsic place within it.

I must admit up front that I am nervous about holding my mobile phone against my ear for long periods. Research has not conclusively shown that radio frequencies emitted by cell phones cause cancer, but it has not disproven it either. So, when possible, I place my phone in speaker mode, especially when I expect to get an automated response to my call, like when I call the pharmacy to check on the status of a prescription.

I did this one morning about a month ago. I touched the various numbers that led me along the path to discovering the status of my order but met with a roadblock on the way, so I went back to the main menu and pressed the number to speak with a pharmacist. A woman came on, and I began to explain the situation to her. Suddenly she interrupted me to bark, “Stop yelling at me!”

I was flabbergasted since I thought I was talking in a normal voice, so I stammered, “I’m not yelling.”

“Yes, you are!”

“Well,” I hesitated, “I have my phone on speaker, and perhaps the volume is too high; let me turn it down.”

“That’s not it, you’re yelling. Just answer my question!”

I meekly asked her to repeat the question, answered it, and was told the prescription awaited pick-up. “Okay,” I whispered and hung up.

Wow, I thought, she’s having a bad day.

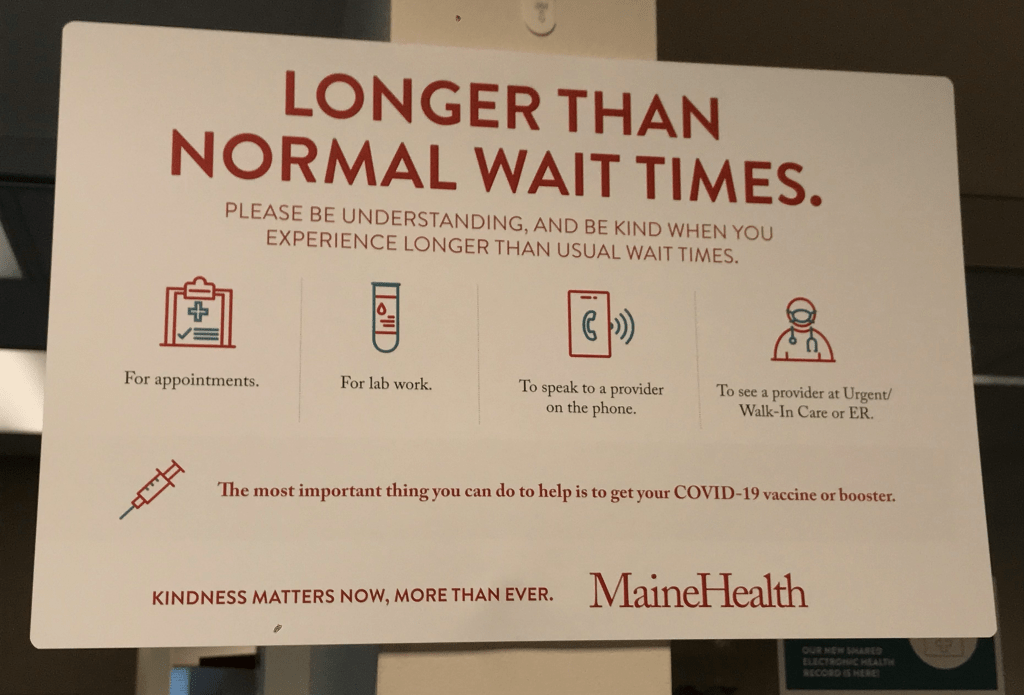

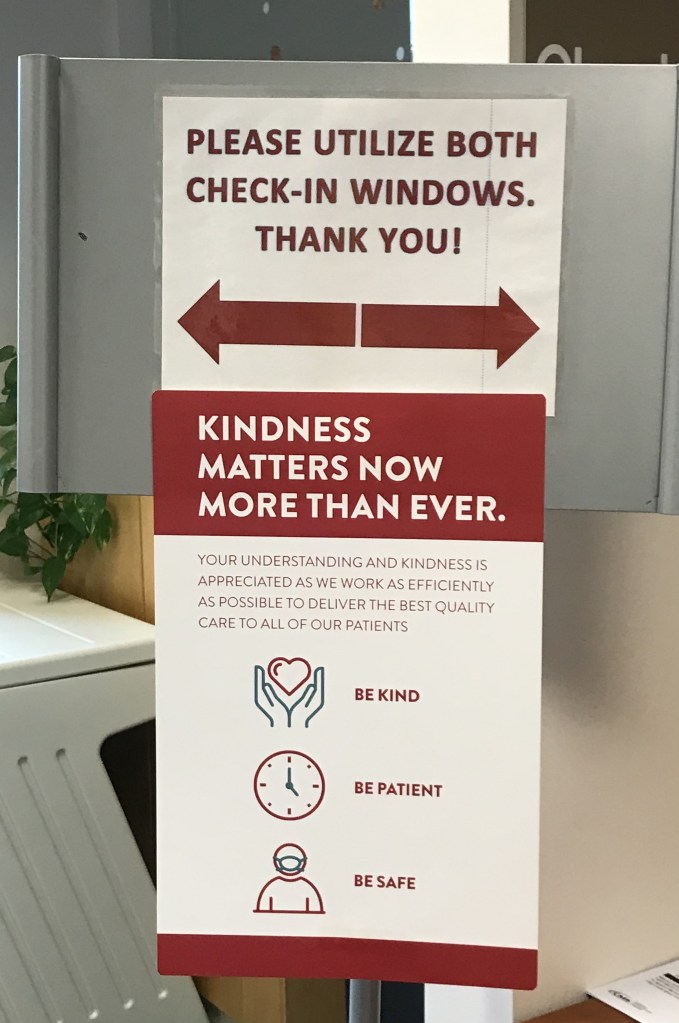

About a week later, I had an unrelated conversation with a healthcare professional in my community. She asked me if I had noticed the signs posted at the local hospital and in virtually all doctors’ offices asking patients to be kind to staff and one another. I had not paid much attention but had a vague recollection that I had seen such signs and that they were also displayed in yards throughout my town. “BE NICE,” “BE KIND,” they reminded. She noted that these signs were relatively new.

Before the pandemic and the concurrent escalating political divide, such reminders were not as necessary because unkindness, rudeness, anger, and frustration were not as prevalent in public as they are now. People, she reflected, are just not as patient and thoughtful of one another as they used to be, and healthcare professionals, while not the only ones encountering such bad behavior, are some of the most frequently abused. The same essential personnel who risked their lives to come to work during the height of COVID, while many of us avoided public places, are being disrespected and insulted. No wonder they are quitting their jobs in droves, she posited.

Her words and the encounter with the pharmacist started me thinking about two things: how little we know about the people we encounter daily and how much we need to give one another the benefit of the doubt in every situation.

To go back to the pharmacist. She had no idea why my voice was coming through the line so loudly; she didn’t know that my phone was on speaker or that my spouse was hard of hearing, and that I habitually speak in a louder-than-normal voice. I didn’t know whether the call she received just before mine had been an unpleasant encounter with a demanding customer or if she was alone in the pharmacy trying to catch up on a several-day backlog of script orders. We experienced each other as impatient and rude, but did we take a moment to consider each other’s circumstances, limitations, pressures, and challenges? Did we assume the other was a good person, needing patience and kindness, or did we conclude that she was obnoxious, demanding, and unworthy of respect? Did we have the capacity to give each other the benefit of the doubt and try to calm rather than stoke the flames of irritability?

A couple of weeks after my conversation with the healthcare professional in my community, I went to a specialist’s office at the local hospital. I saw kindness signs posted at every turn of the corridor, in every elevator, and at three different sites within the specialist’s reception area—a desperate plea to patients to calm themselves and treat others respectfully.

How do we increase our bandwidth for kindness and respect in all the encounters of our daily lives? We can start by getting in touch with our own innate goodness, being kind to ourselves, and understanding where our instinctual and habitual reactions come from. Then, we can assume that the other problematic person is also innately good, dealing with some of the same human challenges we are, and deserves to be cut some slack. And we can imagine walking in their shoes even briefly or shifting to see the situation from their perspective.

Monica Guzman’s book, I Never Thought of It That Way, uses the acronym INTOIT (to capture the title’s notion) and encourages us to be open to INTOIT moments when our perspective is changed, broadened, or softened by seeing things newly through the eyes of another. She encourages us to ask, with genuine curiosity, the fundamental question, “What am I missing?” To acknowledge that the picture in my head is not the complete picture of any person or situation; it’s just my perspective.

We cannot know all the conditions and circumstances that have made someone who they are at the moment we encounter them or why they say and do what they say and do that may aggravate or thrill us. But since we long for understanding and respect, we can infer that they, too, yearn for it, along with grace, kindness, courtesy, and indulgence. As the Dalai Lama says, “Genuine compassion is based on a recognition that others, like oneself, want happiness.”

Kindness is as kindness does. It is not a warm, fuzzy feeling but a way of being and acting. It is not needed now, more than ever, but now as much as ever. Be kind.

I’m sitting on the small beach in downtown Bar Harbor, Maine, on a cool, showery day in late June. My sister, Ann, visiting me from Nova Scotia, has just arrived on the CAT, the ferry between Bar Harbor and Yarmouth. We’ve walked the main street, popping in and out of shops, and are now killing a little time before having lunch at a nearby Italian Restaurant—she’ll tell anyone how much she loves pasta!

Ann saunters down the short stretch of rocky beach, eyes trained on the ground before her, searching for elusive beach glass and unusually shaped and colored beach stones. I’m wearing my navy Sketchers with white soles, and I don’t want to get them wet and dirty, so I have decided to sit still on a large stone at one end of the beach and wait for Ann to carry out her meticulous search.

A few feet away sit two fortyish women, also perched on large stones, chatting easily about summer clothing they have purchased or hope to purchase. A few children—I’m not paying attention—ranging in age from about eight to perhaps sixteen, wander back and forth from their mothers to the water’s edge. A teenage boy settles beside one of the women and sorts through the wet stones at his feet.

All this is happening within my peripheral vision. I’m staring off into space, focusing on my private thoughts, so I only half see what happens next in the twinkling of an eye. The teenager picks up a stone, large enough to fill the palm of his hand, and raises his arm to toss it into the water. He pulls his arm back, but instead of throwing forward, he loses his grip on the stone, and it flies sideways, out of his control.

I hear a crunch, like a finger poking through an eggshell, then a gasp and an “Oh my God!” I focus my attention on the group. One of the women clutches her head in her hands, bright red blood spreading through her quickly matting hair and dripping between her fingers. Her face is pink and blotchy, and she is rocking back and forth, gasping for breath.

“Mom! I’m so sorry. I’m sorry! Mom! Mom!” the boy pleads in a hushed but urgent voice. His mother doesn’t answer. She’s trying desperately to master the pain. The second woman and the children cluster; they whisper urgently to one another, asking what to do. The woman at the center of the circle is silent, rocking. I sit still, saying nothing, willing them to know what to do next. I’m tempted to pull out my phone and dial 911, but I wait. This is their crisis; let them handle it. I have no right to intrude, at least not yet.

“Can you walk? Let’s get you off the beach,” says the other mother. She and the boy lift the injured woman, holding her under one arm and by the other elbow, wrapping arms around her waist. She leans on them, and they slowly and jerkily shuffle toward the parking lot just a couple hundred yards away. As they trudge, the uninjured mother pulls her phone out of her bag, and I hear the beep, beep, beep of the dial tone.

I watch them go, then turn to see that Ann, oblivious to this scene, has almost completed her beachcombing and is ready for lunch. When she approaches, I tell her what’s happened, emphasizing the eerie sound of the stone connecting with the woman’s skull. We talk about how a day, and sometimes a life, can change in a moment—from a relaxed vacation at the seashore to a head injury that may have traumatic and lasting effects. As Ann and I leave the beach for the restaurant, the ambulance arrives, sirens wailing, lights flashing. That family’s day has changed irreversibly, without warning or intent, in the twinkling of an eye.

I cannot get this incident out of my mind for the rest of the day. I wonder how the woman feels, whether she is still in the emergency room or if the injury was serious enough to put her in ICU. Or was it just a minor cut, and she is already back at the B&B with her husband, family, and friends, sipping a cocktail before dinner?

That night I lay in bed before sleep, musing on life’s fragility, insecurity, and uncertainty even in the calmest and most seemingly benign situations. When we wake up each morning, we never know what the day will hold—celebration or grief, joy or tragedy, safety or danger, a new beginning, or a sudden end. I carry my reflections to the extreme, as I am wont to do, and imagine what it must have been like for Jews to wake up in the morning in Auschwitz, wondering if they would eat the usual wormy porridge, freeze while pointlessly hauling heavy rocks, or die in a shower of gas. Or would they see a smile from a fellow prisoner handing them a scrap of bread or hear the sound of the tramping boots of friendly soldiers opening the gates to deliver them from hell?

How do we live with such overwhelming uncertainty? We pretend that it doesn’t exist, that we know what to expect and what the future holds. We forget or do not allow ourselves to remember that circumstances, large or tiny, change in the twinkling of an eye.

After our recent trip to Italy, where my partner spent five days in the hospital with acute asthmatic bronchitis, I grumbled about the time and effort of filing the trip insurance claim to recover the extra medical, food, and accommodation costs. I slogged irritably through the tedious paperwork and bureaucracy, expecting it to drag on for many months. One morning, I determined I could no longer avoid filing what the instructions told me were the last pieces of information necessary to complete the claim. I logged on to the insurance website to do so, frustrated, bored, and tired of it all. Lo and behold, in the twinkling of an eye, my mood and my day changed. The claim status page announced that the company had mailed checks for nearly $1000 more than I had originally claimed. “Hallelujah!” I shouted. We never know, do we?

It’s a truism, and while we are tired of hearing it, the only way to live with uncertainty is to accept it and face it, moment by moment, trusting that we will have the inner and outer resources to meet whatever arises. Let’s not pretend, though, that the unpredictability and changeableness of life are not uncomfortable. Let’s be real. However, the more we try to resist the constantly changing nature of our existence, the more certainty and control we try to establish in our minds or circumstances, the more anxiety we bring to ourselves. The more expectations we entertain, the more disappointment, dread, and suffering we invite.

“Let go, accept, and surrender” are hard words to hear or say—challenging attitudes to adopt. But they, like all new habits, become easier with practice. Embracing life just as it is, moment by moment, can lead to the only security and confidence we will ever know in the face of our groundlessness. All occasions are opportunities for understanding and insight. There is a kernel of goodness at the heart of everyone and everything.

The only truth we can hold onto as things constantly change in the twinkling of an eye is the promise given to St. Julian of Norwich in the 14th century, “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.”