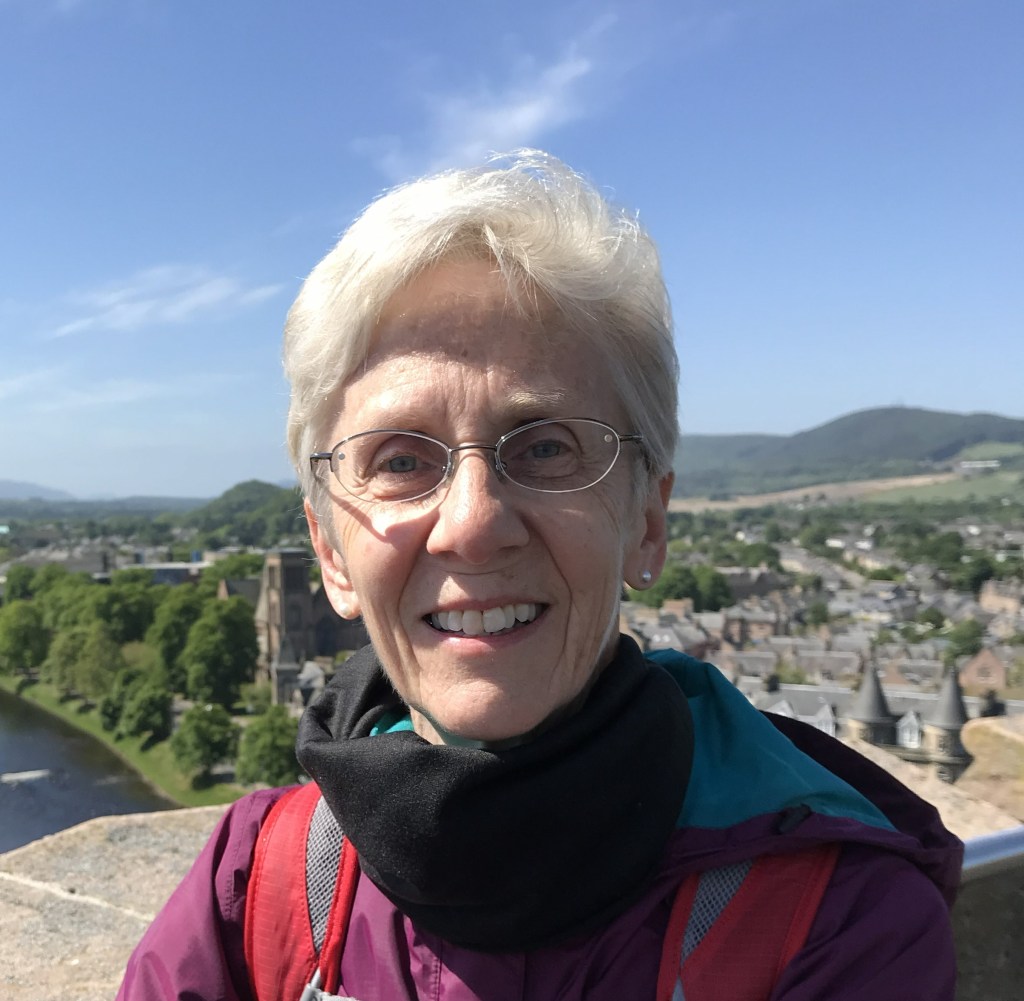

After decades of wearing my hair short because others said it suited me, I finally grew it long—only to discover that the real transformation had less to do with style and more to do with self-acceptance.

In mid-career, when it seemed important to look my best each day, I dragged myself from bed at 4:30 a.m. to shower and “fix” my hair before work. Back then, I used to vow, “When I retire, I’ll grow my hair and put it in a ponytail!” Especially on bad hair days, when no amount of tweaking produced the desired effect, I repeated that promise. At sixty-nine, six years into retirement, I finally fulfilled it.

All my life, people have told me—completely unsolicited—“You look better with short hair.” Some justified their opinions by explaining that short hair frames and softens my narrow face, making me look less somber. Imagine. A haircut can do all that.

I’ve always wanted long hair. The grass is always greener, right? I’m small, and I thought short hair made me look like a boy. In those days, it mattered to me to look like a girl. Still, imagining growing my hair stirred conflicting feelings: self-indulgence and risk. Self-indulgence? How dare I choose what I want instead of what others say is best? Risk? Maybe they’re right, and I would look ridiculous. The project felt too dangerous, so I postponed it, promising myself I’d wait until retirement. Perhaps then, I conjectured, I would care less about how I looked or what others thought. I pictured myself in my senior years as wilder, less risk-averse, less respectable—à la the Red Hat Society. I’ve also daydreamed about spending whole days in my pajamas—haven’t you? But ten years into retirement, I still haven’t done that, either.

As I aged and shyly shared my ponytail fantasies, some asked, “Don’t older women usually prefer short hair? Isn’t it easier to manage with arthritic hands?” Others implied that long hair is for younger women trying to attract men, as if older women shouldn’t care—or couldn’t. I once heard my mother say that long-haired older women are simply trying to prolong their youth.

My reasons for wanting long hair were many. I imagined spending less on haircuts—no surprise for stingy me—and less on hairspray, my chief styling tool. My compulsion to control led me to spray my short, unruly waves into a neat helmet. Yet when the wind blew, my lacquered hair stuck out at spiky angles. Hairspray is a gooey mess when wet and makes hair brittle when dry. Its mist made me cough. Its empty cans clutter landfills. Long hair, I believed, would be more economical, healthier, and more environmentally friendly. Besides, I wanted to relax a little and stop trying so hard. As I grew older, I realized I had fewer years left to experiment in all areas of life—hair just one of them.

At last, I was ready. I found a new hairstylist and confided my secret dream. She was enthusiastic and didn’t subscribe to myths about long-haired older women. We discussed a long-term strategy; I shared my fears and hopes, and she became my biggest cheerleader.

What did I learn as my hair grew?

On bad days, the mirror embarrassed me. One day I’d think my hair looked acceptable; the next, another half-millimeter of growth would plunge me into despair. Somehow, I found the courage to keep going. A week added three millimeters—sometimes enough to make all the difference. “Stay the course!” my stylist counseled.

On good days, I gloried in the drag of a brush through thickening strands or the glee of wind whipping hair across my face, tickling my cheeks and neck. I delighted in sweeping it back with clips and bands, then setting it free to fall around my thin, somber (so what!) face.

What did others think during the growing process? Some joked, “What is an old lady doing growing long hair?” Others asked, “And how much longer do you plan to grow it?” No one was brave enough to say, “I liked it better short,” though some expressions spoke volumes. I steeled myself against discouragement from those not on my team. I told myself this was an exercise in discovering my true self, regardless of approval. But—oh my goodness—two people said they loved it, and I loved them.

As my hair lengthened, I reflected on what I cannot change: wrinkles, scars, age spots, blemishes, and the bags beneath my eyes. The visible residue of traumas, heartbreaks, poor choices, and neglect. Hair, at least, was something I could alter.

Despite my bravado, I harbored a suspicion that what I saw in the mirror was not what others saw. Still, I tried to trust my own eyes. My long hair was luscious and luxurious—if not at this very moment, then surely tomorrow after washing and blow-drying. I accumulated countless clips, barrettes, bands, and scrunchies, convinced that the next accessory would be the perfect solution. My hairdresser bolstered my confidence. “You have beautiful hair,” she insisted.

Twelve months later, I’d had enough.

Once it passed my ears and reached my bony shoulders, I had to admit it wasn’t the look I’d imagined. I’d pictured a high ponytail with wispy bangs and loose curls brushing my cheeks—an older version of movie star Dakota Johnson.

Instead, my bangs were kinky, not wispy. My fine hair fell in lifeless strings beside my exposed, oversized ears, and my ponytail was a stubborn little stub at the base of my skull. Strands clung to my black sweaters and drifted invisibly across the bathroom floor, sticking to socks and shoes. Washing my hair took forever—so much rinsing. My spending on shampoo and conditioner climbed, and I still relied on hairspray for some semblance of control. As I brushed my hair over the sink, I worried about loose strands clogging the drain and the Drano required to clear it.

Finally, one day, a neighbor declared, “Long hair doesn’t work for older folks. You’d look much better with it short.” While I bristled at her generalization—I know many elegant women with long tresses—I had privately reached the same conclusion days earlier. “You’re right,” I replied. “I have a haircut scheduled next week, and I can’t wait.”

Let’s face it, I realized: I am a practical, neat, put-together older woman—not whimsical or breezy. Perhaps long hair doesn’t reflect who I am. I felt both disappointed and relieved; glad I’d tried and learned from the experiment.

So off to the stylist I went. She looked slightly let down but acquiesced, urging me not to cut it as short as before. She clipped and trimmed, turning the chair this way and that to inspect her work. Silently, my silver tresses fell to the floor.

An ear-length bob emerged around my still-thin, even more wrinkled face—a compromise. We agreed it suited me. She swept up the clippings and tossed them into her dustbin—a year’s anticipation and a lifetime of dreaming discarded in seconds.

The long-hair experiment was one way station on my ongoing path toward self-discovery and acceptance. As with most of my experiments, I don’t regret it. I’ve landed somewhere between short and long, control and surrender, convention and rebellion. I’m glad I pushed my boundaries; now I feel a little freer inside them.