I drink Yogi Tea every morning, first thing, right after I feed the animals and take the dog out for his first sniff and tinkle of the day. Just after I ring my meditation bell, turn on three tea lights in front of my Buddha statue, and sink into my seat on the couch, facing the window overlooking our garden. I take a sip of Yogi tea, a deep breath, set my timer for twenty minutes, and come home to myself.

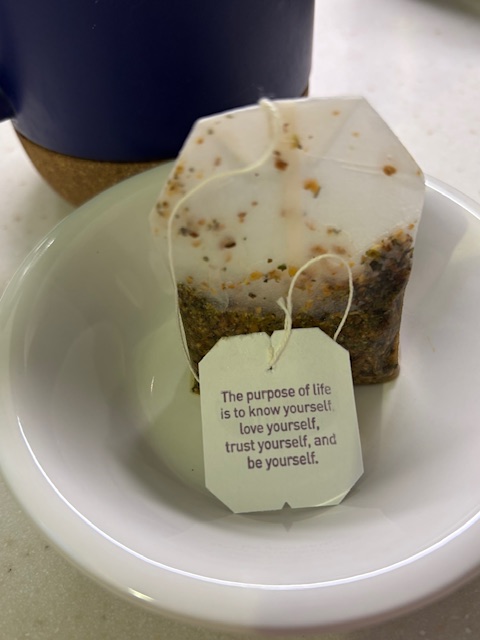

The other morning, as the cats were chowing down and my electric kettle was bubbling, I opened a new tea pouch and pulled out a fresh bag of ginger tea. As I unwound the paper tag attached to the bag by a thin thread, I was astounded to see this message: “The purpose of life is to know yourself, love yourself, trust yourself, and be yourself.”

I’m fond of the word ‘gobsmacked,’ which is British slang for being astonished. I was gobsmacked that the universe had sent me such a message, first thing on a July morning in the politically, socially, and personally turbulent summer of 2025. Right away, I knew it was a message that needed some unpacking, so I settled into my meditation posture—the dog tight to my left thigh, the Maine Coon cat spread across my lap. The black and white cat was, of course, doing his aloof morning meditation on chipmunks, squirrels, and birds at the screen door that opens onto the patio. I took a sip of ginger tea and began.

Know yourself. No problem for me, the most introspective creature on-the-planet, as my friend Bruce would say. Self-examination is my middle name, has been since birth, for good or ill. For most of my life, self-examination has meant self-critique. I have a more than passing familiarity with all my faults, bad habits, propensities, temptations, mistakes, and the karma that results from them. However, genuine self-knowledge or self-awareness has only emerged in later life as I learned to meditate and look deeply at the roots of my motivations—my fears, attractions, and repulsions. That self-awareness, though more true, is also softer, as I’ve allowed self-compassion to touch and soothe the wounds uncovered by my x-ray inner eye. It felt good to have my ingrained habit of self-reflection validated as part of life’s purpose by the Yogi Tea Messenger. Part of myself is okay. Phew! That’s a relief!

Love yourself. My stomach twisted in a knot, and I knew this was not going to be an easy one to delve into. I make this deeply personal revelation only because I suspect there may be a few of you out there who share my experience, and I want you to know that you are not alone. Since early childhood, I have sensed that I am, at my core, a flawed person. There is something wrong with me that makes me do bad things, or, at least, fear that I will do bad things. I think this sense may have come from my mother, and I am certain my Baptist upbringing with its emphasis on original sin reinforced it. I long ago forgave my mother, but I will never forgive St. Paul and the Christian Church for instilling the hideous notion that I was born full of sin. Buddhism, which I’ve gravitated towards in recent years, teaches that we each contain both good and harmful seeds in our store consciousness and can learn to nurture the former rather than the latter.

But let’s not get too theoretical here. Loving myself is challenging! And I don’t believe I am alone with this challenge. Understanding what self-love is and how to practice it will take me the rest of my life and then some, and I’m getting a very late start. But, while breathing evenly and gently as the ten-minute meditation bell chimed, I remembered the self-compassion I congratulated myself on developing as I’ve aged. Let’s start there, add a little self-forgiveness, tenderness, thanksgiving—whatever else might water those tiny seeds of goodness the universe has planted in me. I recalled my connection to all the beauty around me and recognized that I am made of the same stuff. Soon, I thought, I may have enough confidence in my basic goodness to…

Trust myself! Again, the passage of time, also called aging, is of some help here. It teaches lessons of humility but also repeatedly validates my intuition, my gut, or bodily intelligence. As I’ve looked back over my life, I’ve seen instances where I had a premonition, an insight, or an inner sense about the reality of a situation, the right course of action, or an action to avoid. Sometimes I heeded the hint, and other times I ignored the impulse. But time and again, what my body intuited was revealed as events unfolded. I pay more attention to my un-rational intelligence these days. The more self-aware I am, the more I accept and love myself, the more I can trust myself to make the right choices, the life-giving, kind, and just ones. And I understand these three—self-awareness, self-love, and self-trust as inextricably linked, forming the foundation on which I can…

Be myself. What a sense of relief and ease washed over me as I entered the home stretch of that morning’s meditation. I paid attention to my body, as I set my imagination free to envision what it might be like to be who I truly am, instead of who I or others expect me to be. I noticed a sense of effortlessness. Straining and striving melted away, replaced by an unhurried settledness. A pervasive feeling of well-being and wholeness refreshed my tired mind and body. Yet, on the horizon, I saw the tremendous responsibility of freedom dawning, and I experienced a charge of fear, like a tiny electric shock—joy and sadness, pain and pleasure co-arising and interdependent.

The meditation bell chimed three times, signaling the end of twenty minutes. I breathed out, letting go, and lingered for a few moments longer in the silence and stillness. Then I lifted my cup and took a long, full gulp of still-warm tea while reciting the Tea Messenger’s morning wisdom one more time: “The purpose of life is to know yourself, love yourself, trust yourself, and be yourself.”