Continued

Solitude

At home, I am not solitary. I live with my spouse, my dog, and two cats, in a vibrant retirement community in a college town where intellectual work, art, theater, and music flourish. Tourists stroll the streets in summer. I am always meeting people I know well—or not at all. This social identity feels so natural, so me, that it is hard to believe it is constructed or conditioned.

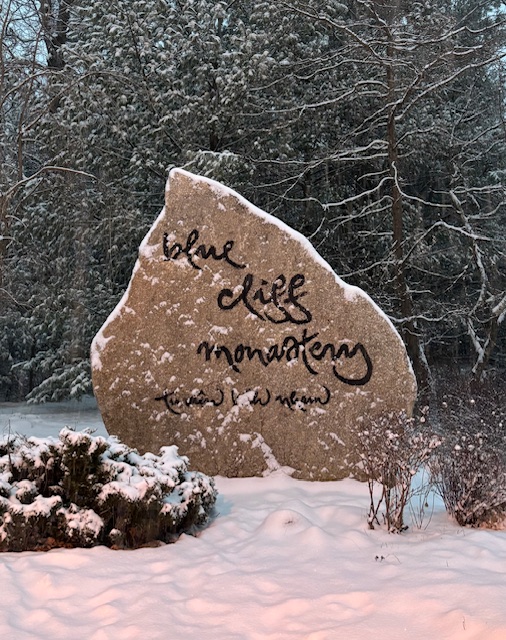

Entering solitude, for me, is like going home. Though I am far from my physical home, I feel more at home here. Alone, I am more aware of my feelings, more curious, open, at ease, and forgiving. In the quiet of this cold winter morning, I ask: Who is my essential self? Is it distinct from my conditioned self? Does my essence emerge in solitude, or in relationship with others, or somehow in both? The witness self—the continuous, conscious observer—appears more readily for me in solitude.

Still, I must be careful. I am convinced that truth lies in balance rather than extremes. Perhaps I value solitude so deeply because I have so little of it.

Stillness

I arrived with the hope that my days alone would be unstructured, guided by the heart’s promptings. I imagined staying in my pajamas all day, doing nothing at all. That fantasy dissolved when I decided to bring the dog. I have meandered from one activity to another, discovering that it is far easier to imagine being still than to be still.

What do I want from stillness? The word that arises first is settling. I long for the persistent sense of inner agitation to give way to calm. Through meditation, I have learned that this happens when I sit still for long periods. Buddhist teachings liken the mind to a muddy pond: when left undisturbed, the sediment slowly settles, and the water clears. In my own experience, my body settles first, then my mind, and finally my emotions; clarity emerges.

With clarity, my actions become more intentional. This week, in my efforts to be still, I have taken special care to cook nourishing food and arrange it beautifully in the mismatched bowls and plates I found in the cupboards. I eat slowly—and, of course, silently—savoring each mouthful, noticing flavors and textures, surprised and grateful. No conversation distracts me from chewing thoroughly, to the relief of my delicate digestive system.

I read slowly, reflecting on what I read, appreciating the symmetry and beauty of language, and letting words sink into my consciousness, hoping they will water the seeds of my own writing.

Slowness, I tell myself, is the first step toward stillness, as the dog and I head out on our thrice-daily walks. Snow, ice, and mud slow us down, and we accept and adapt to them all. He stops often to sniff each new scent. I stop too—standing still, looking around, breathing, inhabiting the moment.

Fast and slow, motion and stillness, cannot exist without each other. Neither is inherently good or bad; each has its season, even if I have my preferences.

Silence

It almost goes without saying that outer silence supports inner silence. Alone and still, silence becomes tangible. I soak it in, treasuring it. I resent the heater kicking on with its low hum, the sound of the upstairs neighbor’s truck pulling into the driveway, his boots pounding up the stairs, the clicking of my keyboard as I type. When these sounds subside, I sink into the silence and luxuriate in its nothingness. It wraps around me like the heat in an empty sauna.

For a moment, I imagine never speaking again, never hearing another word. I contemplate the silent emptiness of death, and while I imagine it, I notice a quiet gratitude arise. Then the heater kicks on once more, and I feel my body tense—just slightly—reminding me how much stress accumulates when we are constantly bombarded by sound. How restorative silence feels, with its sisters, solitude and stillness.

And yet, silence is not the same for everyone. If I could not hear, would I long for sound? My partner is functionally deaf. Without her hearing aids, she hears nothing at all. Deaf since early childhood, her experience of silence is marked by alienation, misunderstanding, and disconnection. For her, sound can be orienting and connecting—or overwhelming. She reminds me that silence, like solitude, is not inherently sacred; its meaning depends entirely on context.

As I bring these reflections to a close, I search my OneDrive for a poem I wrote some time ago and read it carefully, recalling the feelings behind the words.

THREE MAGI

Stillness

Silence

Solitude

Three Magi, wise and noble,

Enticed

By intuition,

A common secret dream.

Set off to find the source of all that Is—

of love,

of hope,

of truth.

Stillness ambles imperceptibly.

Motionless, she travels far—

deeper,

nearer,

clearer.

Silence speaks no words,

Adds nothing to the frantic roar

of hate,

despair,

and lies.

Solitude bears destiny as she strides forth.

Knows birth and death and all between alone. Her heart

a pulsing,

throbbing,

longing.

Three Magi,

seeking their soul’s star,

walk home.

What is the soul’s star I seek during this week of stillness, silence, and solitude? As I ponder the question, my witness-self watches thought-clouds drift across the sky of my mind: essential, real, true, authentic, love, compassion, home. Any of these could be my soul’s star. And these three wise magi—Stillness, Silence, and Solitude—are my companions and guides as I walk home.

I rise from the computer and walk slowly to the kitchen to boil more water for tea. The kettle whistles, breaking the silence. The dog stirs, stretches, and hops down from his chair to follow me. I look out the window at the fresh snowfall, still undisturbed. I remember that I have a few more days alone before rejoining those whose lives are bound to mine. I give thanks.

I give thanks.

Author’s Note

This essay grew out of a week-long solitary retreat in central Maine in 2023, and reflects my ongoing spiritual inquiry into stillness, silence, and solitude. Written as contemplative nonfiction, it blends my lived experience with reflective practice. My intention is not to idealize the three s’s, but to examine what they offer when approached with curiosity, humility, and balance.