Your Boulder

A hint for those who have difficulty commenting on these posts: Click on “Read on blog” at the top right of this email, and you will be taken to my blog site. Scroll to the bottom of the post, and you will have the opportunity to reply. Happy commenting!

*******************

Ajahn Chah, a Thai Buddhist monk of the Forest Tradition, was walking through a field with his disciples. They came upon a large boulder, and he asked his followers,

“Is this boulder heavy?”

They responded, “Yes, teacher, it is very heavy.”

Ajahn Chah smiled. “Only if you try to pick it up,” he said.

****************

Only if you try to pick it up.

If you stand on it and look around, you can see farther into the distance, and you might get a sense of the bigger picture.

If you gather sticks and build a fire on top of the boulder, the fire may serve as a beacon, drawing others to this place.

If you lean your back against it or sit on it, you can rest.

If you take a chisel and chip away at it, you may find precious minerals inside or create a beautiful sculpture.

If you hide behind it, you may find solitude, shelter, or safety.

If you plant flowers around it, you will create a garden.

If you join hands around it, you may find friends and build community.

Oh yes, and if you lift it together, combining your strength, ingenuity, and shared intention, you may discover it is lighter than you thought.

Here’s a boulder? What will you do with it?

What Now? Reprise

It’s been over a month since I posted here and over two since I wrote the first “What Now?” article. Honestly, I don’t know what to think or say about anything these days. I’m tongue-tied. That’s as it should be, counsels the Tao te Ching: “Those who know, don’t talk. Those who talk, don’t know.”

Each morning, sometimes before and sometimes just after my meditation time, I read Heather Cox Richardson’s daily newsletter, Letters from an American. I choose to follow her rather than some other news commentator because I like her framing of current events in the context of history, and she’s a Mainer from near my home. Her newsletter and listening to the occasional few minutes of NPR while driving are my meager attempts at awareness of significant events in our country and the world. Like many of my friends, I feel a responsibility to be aware but cannot cope with more intense and in-depth exposure to the news. It is too depressing, frightening, and immobilizing.

As I’ve grown older, I’ve identified and clung to specific anchors that steady me in times of turmoil like this one—help me rise and fall with the tides but keep me from drifting in rough currents. Some anchors are rituals or repetitive practices that calm and focus me. Some are objects or words that inspire or guide me. I’m always looking for symbols that help me make meaning and keep me steady.

A few weekends ago, I visited Blue Cliff, a Vietnamese Buddhist Monastery in upstate New York. The monks and nuns who live there practice the Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhist tradition. That weekend, they were celebrating the third anniversary of his death, or “continuation” as they call it. Besides a few American Buddhists from Maine, Vermont, and elsewhere, dozens of Vietnamese Americans from the New York-New Jersey area came to meditate, chant, hear Buddhist teachings, and eat delicious Vietnamese food. I was fascinated by the rituals and chanting, curious about the customs, and delighted by the food. It wasn’t the sort of silent, secluded retreat I typically seek or enjoy, but it had a simplicity, pageantry, and wisdom that moved me deeply.

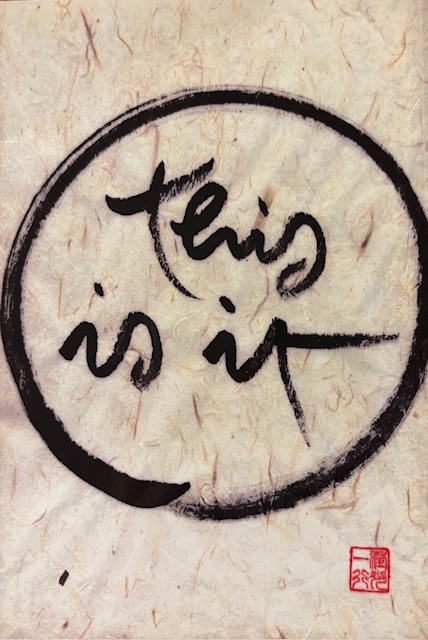

One of the most potent takeaway images from the weekend was this wooden calligraphy panel that focused the eyes immediately upon entering their exquisitely designed meditation hall.

I was awestruck the moment I saw it—so profoundly true and precisely the message I needed to receive, an anchor I could cling to. This Is It. This moment, this place, this situation, this country, this world—this is all there is. So, stop wishing for this to end, for something else to come, to be somewhere else, to be rescued from this current calamity. This is it—the only thing you have to work with, the only reality, your only opportunity. So, embrace it, celebrate it even. Open your eyes, ears, and heart, let the right action arise within you and proceed from you, and let go of the burden of the outcome. This is it. Nothing more, nothing less, nothing other.

For an hour on Sunday afternoon, their gift shop was open for guests to browse and shop. I went looking for a token of the message I had received and found this simple postcard in Thich Nhat Hanh’s calligraphy. I purchased it and brought it home to place in the window opposite my meditation seat so, as candles flicker beneath it and the sun rises behind it each morning, I can look at it and beyond it to what is outside my window.

This Is It—the only time and place I have. I am surrounded by the only people I can respect and love. This is the only moment when I can recognize beauty, speak the truth, be kind, and do justice.

The World is Coming Apart at the Seams

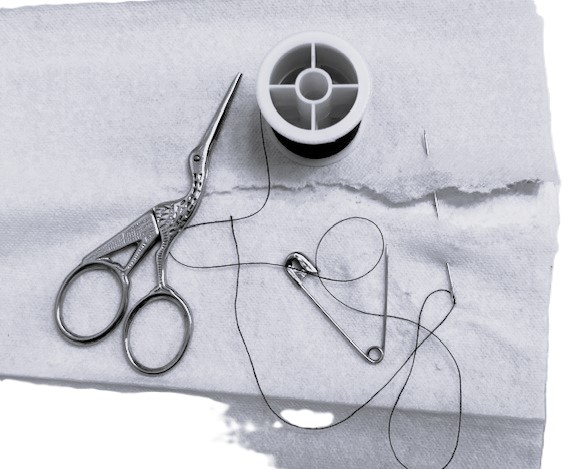

The world is coming apart at the seams.

A stitched and restitched garment

Now, tearing

Everywhere.

I awake from tossing and turning,

Sleep that gives no rest,

From dreaming a companion seamstress,

Abandoned me midst ragged scraps.

My body is heavier than a mountain.

The weight of grief and hopelessness,

Countless tons of it,

Pins me, motionless to my bed.

But I must rise and stitch,

Though the garment is split far beyond my skill—

Rips gaping and subtle,

Ancient and new,

Fissures spread across the earth,

Among and between the nations

And now to us.

My thread is thin and frayed,

My craft, rudimentary and crude,

My tools modest:

Needle, thread and vision:

Do no harm.

Ease suffering.

Embrace what is and learn from it.

These, my implements for mending.

With them I practice sewing.

Insert the needle gently,

Draw thread

Through tattered fabric,

Hold it tenderly,

Mending its ruptures.

Come seamstress, tailor, join me.

Draw threads of love and beauty,

Kindness, patience, truth,

Through our torn world,

Stitching it back together again.

What Now?

With All Due Respect has never been, nor is it about to become, a forum for expressing political opinion, mine or anyone else’s. However, I don’t feel I can overlook the outcome of the 2024 election at this web address. Its effects are too far-reaching to ignore completely. The people of the USA have elected a president who aspires to become an autocrat, a person ruling with unlimited authority. (Merriam-Webster Dictionary.)

I am bewildered by this outcome and have spent considerable time and mental effort in the last three weeks trying to understand how and why it occurred, though my gut always told me it was a strong possibility. I’ve listened to the various theories apportioning blame to politicians, political parties, educational elites, globalism, immigrants, and the “woke” culture, but I’m still baffled. I’m entertaining the possibility that I might never understand.

I’ve spent early morning meditation sessions asking myself what this new reality in America might require of me, a white woman, moderately well-educated, of the middle class (with working-class origins), a 72-year-old lesbian living in the relatively liberal southern part of the conservative state of Maine. Oh, and I also identify as a former Episcopal nun, now a practicing Buddhist-cum-Taoist.

I’m looking for an anchor to help me move forward into the unknown, changing, uncontrollable, undoubtedly challenging future. I want to do so with integrity, courage, and hope, but frankly, I’d just like to know how to put one foot in front of the other and not make a mess of things.

For the last two years, I have done the same thing each morning when I get out of bed. At home, this ritual is preceded by feeding my dog and two cats, making tea, and turning on my heating pad. I then stand before my stone statue of the Buddha and sound my singing bowl three times, sending delicately beautiful vibrations out into the universe, my way of greeting the new day. Next, I light three tea lights (no live flames allowed in my retirement housing) and recite three commitments for the day.

When I am away from home, my routine gets simplified. I just call the intentions to mind:

- Do no harm

- Help others

- Embrace the world just as it is, using everything as a means for further awakening.

Invariably, as I turn to walk across the room to my meditation seat, I become aware of some fresh insight, a spring of hope, or a surge of encouragement. I developed this daily practice after reading the Buddhist nun Pema Chödrön’s book, Living Beautifully With Uncertainty and Change. The book expounds Tibetan Buddhism’s Three Vows or Three Commitments. According to Chödrön, they are “methods for embracing the chaotic, unstable, dynamic, challenging nature of our situation…”

Sound like our situation? Yours and mine?

Recalling these commitments at the beginning of the day for the last nearly eight hundred days has provided a much-needed anchor amidst the exigencies of my life. On many mornings, they have pierced the prison of my limited perspective and illuminated a path forward when I have felt trapped, confused, misunderstood, vulnerable, tired, and scared—pretty much how I have felt ever since November 5, 2024.

The first vow or commitment is to do no harm in thought, words, or actions. I think of it as the refraining vow. If I can’t figure out how to think, say, or do good, helpful things, can I at least refrain from doing anything? After years of practice, I’m getting a little better at sometimes shutting my mouth and doing nothing. The thought thing is still beyond my reach.

The next vow is to help others. This one can be problematic for me, a compulsive caregiver, intervener, and do-gooder. I add the words “if you can” to the vow. It’s what’s known as the “Bodhisattva Vow,” the orientation towards opening our hearts in compassion for everyone to relieve suffering in the world.

The final commitment is to embrace life just as it is, using everything that happens to wake up and become more self-aware. This is the most fruitful of the vows for me. Sitting across from the three flickering candles in the early morning darkness, I often ask myself, “What does this situation weighing so heavily on my heart and mind have to teach me about myself? How can I see the truth about myself and respond with self-compassion, the will to change, and the patience to start anew?”

So, back to my original questions, “What now? What might this new reality, the second presidency of Donald Trump, require of me?” After lighting the candles and reciting the three commitments this morning, I made a list: respect, simplicity, moderation, generosity, truth, courage, kindness, and resilience. I’m confident I will add more qualities as the new reality dawns. Or is it new? Will it require anything that every day of my 72 years has not already called for?

- Do no harm.

- Help everyone.

- Embrace life just as it is.

The Art of Life

Boston, South Station Bus Terminal, Peter Pan Bus Line, August 15, 2024.

Anxious, tired, embarking on an unfamiliar journey. I sit—rolling suitcase parked in front of me, heavy backpack drooping from my thin shoulders, iPhone in hand with QR code for boarding queued for use—trying to take up as little space as possible in the waiting area and the world. My fellow travelers are as silent, anxious, and self-absorbed as I am—our noses all pointed towards our screens, lost in texts, music, or internet searches, earbuds contributing further to our intentional isolation.

I look up as a dark-clad figure passes the window before me, separating the waiting area from the boarding dock, where the bus will arrive in minutes. The man lopes gracefully, quietly pulling a large utility cart behind him. He pays no attention to the passengers waiting on the other side of the window, and none of us pay him any mind either.

I’m only vaguely aware of his presence until he removes a long pole from the cart and attaches a dripping, soapy white window scrubber, which he draws from the bowels of the cart with the dexterity of a magician pulling a bouquet out of a hat. What rivets my attention in these first moments is the fluidity with which he attaches the scrubber to the pole. He presents himself to the first in a row of grimy windows, and, with a well-rehearsed and measured flourish, swishes the plush tool back and forth on the dirty glass, his body flowing with the movement of his arm, the bubbles on the panes lining up in precise rows each about twelve inches wide.

I am watching an artist at work, and now I cannot look away. He dances along the row of windows, spreading suds over the top half of each, covering the entire set in under a minute, pausing briefly to examine and correct his work here and there with another stroke or two. From my side of the window, I can’t imagine what flaw in his artistry he has detected and repaired. Then, plop goes the scrubber back into a bucket in the innards of the cart, and out from behind him, a pocket perhaps, he draws a squeegee, flips it in the air, and catches it with precision.

Almost before the bubbles on the windows burst, his arm sweeps, with delicate pressure, back and forth across the surface of each pane, creating a clarity I would not have believed possible. He brings the blade to the exact edge of the glass and deep into each corner so that no drip or smudge remains. He stands back and examines his work with the refined eye of an art critic, seems to judge it satisfactory, and then repeats the entire process with the bottom half of each windowpane, his laser attention, poised relaxation, and complete dedication to excellence not wavering for a single second.

I sit, mesmerized by this performance, feeling that I am in the presence of a master who has studied his craft intently with an innocent dedication to excellence. No one else lifts their head from their phone.

The incoming bus arrives, the driver emerges, and a few passengers debark. They retrieve their luggage from the underbelly of the still-humming giant, and the outgoing passengers crowd the door to the boarding platform. The window artist gently places two tall yellow hazard pillars on the concrete platform to alert wayfarers to wet pavement. He adjusts them several times, looking around carefully to judge where an oblivious traveler might place an unwary foot. Then he steps aside, at ease in his invisibility.

I’m in the middle of the line of those embarking, and in the bustle of QR code scanning, luggage stowing, and seat choosing, I lose track of the window artist; my anxiety about decision-making and getting things right blinds me again. But once we pull out of the station onto the southeast expressway, I take a few deep breaths, reconjure the window washer image, and secretly smile behind my N95 mask.

I feel the gods have smiled on this journey, fortuitously begun by watching another human give his very best to an ordinary act of labor, transforming it into a labor of love, a dance of dignity, and an icon of respect for self and others.

Out of the Ordinary: the sacred in the mundane

I enter the Japanese Garden through the Shinto Gateway, the Torii, which marks a transition from the mundane to the sacred. This morning, I’m not looking for the sacred but simply a place to rest my eyes, mind, and body. This particular Torii resides in Stanley Park, in the Western Massachusetts town of Westfield, what I have dubbed the “middle America of New England,” where conservative values, working-class families and businesses, community spirit, and the American dream appear to be embraced with gusto.

Beyond the gateway, robed in every shade of green, lies a perfectly proportioned landscape. Thoughtfully placed benches, most sporting plaques in memory of departed loved ones or honored benefactors, nestle in shady patches. Smooth and jagged stones are strategically placed to delight the eye. Manicured trees, reminiscent of bonsai, glow green in the early morning sun. Flowing Japanese-style structures blend with the scenery. Simply elegant bridges span bubbling streams.

I stroll lazily, framing the natural beauty in my lens, noticing the coolness of the air on my skin, hearing the burbling brooks, and delighting in the shapes, sounds, and freshness around me.

A middle-aged woman in a floppy sunhat, sweating from the exertion, pushes a large stroller along the path. A grandmother with twins, I think. I say good morning, wanting to acknowledge that we are sharing this earthly space. I had consciously decided to greet each person I met this morning, looking them openly in the eyes. She pauses and responds. I notice that it is not children, but a white-snouted dog enclosed in the mesh stroller. I compliment her on the ingenuity of this arrangement, and she explains with a fond smile that her old dog enjoys the outdoors comfortably while she gets her morning workout.

I wander downward to the floor of a small valley and along the edge of a dancing stream. Ahead of me, a young mother with her toddler son uses the activity paper she picked up on the way into the park to point out rocks, water, plants, insects, and squirrels. Her bare arms are tattooed colorfully, and I bristle momentarily. But my curiosity overcomes my distaste, and I wonder what has caused her to decorate her body thus. I’ll Google later, I promise myself, and ask why tattoos are so popular these days.

Following the brook, I come to The Braille Walk—a short section of the path set off by a knotted rope. Next to each knot is a sign in English and Braille describing what a blind traveler might hear, smell, or sense in her immediate surroundings. I think how lovely, how inclusive.

It’s quiet, uncrowded, bright, clear and cool. A waterfall rushes joyfully down into the first of two large artificial ponds, turning a waterwheel on its way. Ducks swim passively. Single parents with single children wander aimlessly. Canadian geese, who had been feeding in the field beyond a few moments ago, fly honking noisily overhead and land gracefully among the unfazed ducks. A sign begs the guests in this welcoming corner of the earth not to feed bread to the birds, causing disease and death, but instead, to buy a small handful of proper food for fowl to cast on the waters.

A wooden boardwalk borders the upper and lower ponds. Like other wanderers, I peer over its railings to the brownish depths below, startled by what I find. Dozens of enormous koi, speckled white, black, and red, swim lazily along the shore, looking for a handout. They weave past each other endlessly and gracefully, parting the muddy waters. I stand, relaxed and delighted, wishing for someone to share this perfect moment in time and space—longing for someone beside me, to echo my smile and look deeply into my eyes, reflecting what I see, knowing what I know. But life has taught me no one sees exactly what I see and feels what I feel, so I pull back inside myself and gaze at the large, lumbering fish, appreciating their patience and calmness.

Two dogs pass each other and me on a bridge; one is a large boxer whose owner mumbles to it urgently in a foreign language. The other, serene and beautiful in its sleek black and white body, sniffs my leg as it passes. Good morning, I say to its owner, and he responds in kind. I tell him his dog is beautiful, and he says thank you.

Pads crowd the lily pond, but no lilies. I walk over its arched stone bridge and into the bright, undappled sunlight, away from the tended, managed, perfectly curated gardens and water features along the path to the wilderness sanctuary. This stretch is even quieter, except for the mild and unintrusive hum of distant traffic. Trees shade the way, but a closely trimmed lawn carpets an intentional clearing near the entrance. The sun beams down on the dew-laden grass. I think it is the perfect place for a picnic, but move on.

I meet no one. The river meanders on my left. The path slopes down. Mud from the recent rain makes it necessary to pay attention to where I place my feet. I come to an opening in the trees, a collection of large rocks on the riverbank, and stop, knowing I must turn and retrace my steps before my aching back, tired legs, and the slight chill on my skin strain my enjoyment of this place.

And so, I do turn, walk up the gentle slope, back past the sun-warmed clearing, across the stone bridge, up several tiers of terraced steps, and towards the rose garden at the top of the hill.

I need to use the toilet. I skirt the party venue, the concert venue, the manicured gardens of brightly colored annuals, the rose gardens far past their prime, and the formal fountain. I arrive at the spotless restrooms, where I relieve the building pressure in my aging bladder.

Relaxed again, I walk back the way I came. As I pass the wedding venue, I see two middle-aged Indian women in Saris and hear them chatting in their native language. The nearby clock tower tolls the half hour. Beneath it, a family of tourists takes photos of itself and speaks excitedly in what, Polish?

Again, I slowly and cautiously descend the stone stairway, which minutes ago I climbed, to the bottom of the narrow valley, to the ponds, the waterfalls, the streams, ducks, koi, and geese. A cluster of families with young children gathers on the pathway to the covered bridge—a gaggle of geese and kids are making an awful commotion. I pick my way between them, careful to avoid goose splat, pass through the coolness of the shaded bridge, and climb up the other side of the valley, wending my way back to the Japanese Garden for one last glimpse of order before I depart. A family sits on a ledge overlooking the falling water—an elderly man in a wheelchair decked out in sweatpants and slippers, a husband and wife, and a small child. I wonder if this is a Sunday morning outing for Dad, who may live in a nearby nursing home. Again, good morning, I say, and they smile.

Tired, satiated, and quiet within, I approach the end of my stroll—the Torii Gate, where I began. I sit briefly on a sun-warmed bench overlooking Stanley Park, a modern-day Eden where the ordinary and the extraordinary are interwoven. I think of the words from the creation myth in Genesis, chapter one. “God saw everything God had made, and it was good.” I also think of the part of the story that tells us we are destined to tend and care for, protect, enhance, and love the goodness of which we are an integral part. I breathe in the variety, the abundance, the freshness, the vitality surrounding me in that ordinary moment, and it is, indeed, supremely good.

(Thank you to Nancy S., who encouraged me to write about this sacred moment.)

Reader Comments on The Blue Room

The Blue Room is wonderful. It is gripping. I intended to read for a few minutes and could NOT put it down. I forced myself to stop about halfway through because I was hungry. I can’t believe this is your debut novel. I would believe it if you said this was your fifth or tenth book. It is lovely, soft, precise, strong, enrapturing. –Corinne E.

*****

I finished your book last night. I got so enthralled I stayed up late to finish it. I really enjoyed it! –Nancy Collins

*****

What a wonderful novel you wrote! It spoke totally to me, and I am going to read it again, leisurely so I can benefit from it and also write to you with details of what moved me the most. I hope you are considering writing another one! –Pilar Tirado

*****

I wanted to tell you how much I enjoyed reading The Blue Room. It left me wishing for my own such space…Congratulations on your accomplishment! –Mary Born

*****

I just finished reading The Blue Room. I …am so impressed at how you fleshed out the story. Your emphasis on detail and colorful prose captured Kathryn’s essence and made her very believable and real to the reader. I guess knowing you and sharing our experiences with the writing group, I can, with empathy, understand the hard work and the commitment you gave to creating the book. You did a superb job and brought light to a topic that we need to know more about. –Deanna Baxter, Author of Willows By Flowing Streams

*****

Finished The Blue Room yesterday. Read it in 3 sittings. I enjoyed it a lot. I knew the writing would be clean: yours always is. It also flows well…I’m sympathetic to the characters—even Mom, eventually. So, good job staying away from stereotypes. Perhaps because I’ve been having back problems all week (my chronic pain, I guess)—I read some of TBR on my back in bed yesterday—I especially liked the latter part of the book on Kathryn’s fighting back against her pain, and also the chapters on her chronic pain group. There, I think, is your audience. –Richard Wile, Author of The Geriatric Pilgrim and Requiem in Stones

*****

[I] wanted to tell you how much I enjoyed and appreciated your new book. I always knew you were an excellent journalist and academic writer, but congratulations on such a powerful novel, which I think will be of help to many people. –Anita Marson Deyneka, Author of I Know His Touch and A Song in Siberia

*****

I finished The Blue Room this morning. WOW, and congratulations. What a stunning, often heartbreaking journey through pain, both of the soul and body, you have shared with us. Thank you! I couldn’t put it down for the past two days. I need to sit with it and let it all sink in. The story you have told is very impactful. I had no understanding of chronic pain prior to this. My heart goes out to you and those who suffer and live with such pain. –Sandra Eldred

*****

What a book you have written! I like the rhythm of your prose…it changes smoothly when it needs to. Your writing is highly readable, so the reader can easily keep pace with the story as it moves ever forward.

There is so very much in the story that is familiar to me! The time frame, the cars, the housing conditions, clothing and hairstyles, the methods and thinking and attitudes around work, school, family, gender roles, teaching, education, behavior, morals, and discipline—it stirs up so many memories—not all of them good.

This is a story that must resonate with a large fraction of the women of the world. Or at least the Western world. Western society lays relentless, conflicting, and impossible demands and expectations on women of every type, at home, at work, and in the wider community. Many spend all their lives and every iota of energy meeting the wants, needs, and expectations of everyone around them, but rarely for themselves. It is toxic, draining, and damaging. And we blame ourselves, second-guess ourselves, and believe that somehow it is all our fault.

All this to say, WELL DONE YOU!!! You must be very proud of what you have accomplished. Writing is hard work. Doing it successfully is harder still. Thank you for involving me a little bit in the birth of your book (it was great fun!) and for the lovely acknowledgment you have afforded me. –M.L. Whitehorne, Cover Artist and Astronomer

*****

Deepest Longing, Greatest Fear

Roaring breakers,

Pound t’ward the land.

Bare icy feet

Stride ‘cross the sand.

Clean bracing wind

Whips strands of hair.

Streams past my ears,

The whistling air.

Bright sunbeams strike

My smiling face.

Sky’s azure blue

Wears clouds of lace.

Ocean’s deep thrum

Brings bubbling joy,

But freezing fear

Delight destroys.

That day, I walked

The beach alone

I saw at last

What I most loved—

Eternal sea

And boundless waves,

Sky blue, sun’s diamond

Rays above.

And yet, that day

I also knew

The end of me

I dreaded most—

To drown at sea,

Ice cold and tossed,

While choked the breath

From my life’s throat.

This truth, I see,

As I grow close

To death’s embrace,

Oh, dread delight.

We fear the most

Our hearts desire,

We love the most,

What we most fight.

We deeply long

For home. Go home!

One with the Source

From whence we came.

Our greatest fear?

To lose ourselves

Absorbed into

Life’s force again.

Annihilation—

Love’s abyss.

Union—

End of separateness.

The Relief of Letting Go

My friend, Jim, is a crotchety nonagenarian. He has been crotchety his entire life, more or less charmingly so in his youth but annoyingly intensifying as he has grown older. Like many his age, he has consigned everything modern to the rubbish heap and glorified everything he remembers of the good old days. As he has aged, he has grown more self-centered, believing his views are the only correct ones, his tastes are the most tasteful, and his ways of doing things are the only sensible ways. Some of his ways of doing things involve growing his hair and beard long, eating sausage for breakfast every morning, and devouring an entire quart of ice cream at a sitting.

Jim’s health has been gradually declining, and he is less able to care for himself. The decline is noticeable to everyone who sees him regularly, but he won’t admit it. He insists that he can live independently, make all his own decisions, and do so ad infinitum. He believes he does not need to change anything about his life and has gruffly rebuffed all attempts to hire caregivers or suggestions he move to a more supportive living situation.

A little while ago, Jim fell and broke his collarbone. Overnight, he could no longer cook his breakfast sausage, pull up his pants and put on his suspenders, write his checks, or accurately sort his medications. His family bravely and good-naturedly stepped in and did what they had wanted to do for quite some time. They took over his finances, cleaned up his apartment, sent him for a haircut, and insisted he move to assisted living, at least for a month of respite care, until his collarbone healed and he could be reevaluated for independent living. He did not enthusiastically embrace this plan, but surprisingly, he acquiesced more quietly than expected.

When I visited him in his new efficiency apartment, I was amazed at the transformation. He was more cheerful than I had seen him in years. The boundaries of his life had shrunk to a one-room studio, with a huge closet containing a few of his clothes, a TV with minimal channels, three meals a day served in the facility’s dining room, medications delivered and taken on time, and lively interactions with the staff. They take him for who he is and chide and prod him in a no-nonsense fashion. He mentions a couple of them fondly. He is less isolated than he was when living alone, though he still stays in his room most of the time.

I ask him how he’s doing, and he jokes about not knowing what will happen to him, so he doesn’t bother thinking or worrying about it. One of his children has taken over his finances, and he has no idea how the bills are being paid or how much money is in his bank account. His life has become simpler. The staff takes him to meals, helps him to bathe and dress, and transports him to doctor’s appointments. They do his laundry and give him his pills. He just goes with the flow. Finally, after months of resistance, he has learned to use his cell phone because it is now the only way to stay in touch with family and his few remaining friends. It’s all okay, he says lightly.

I reflect back to him that he seems more peaceful, and he doesn’t disagree. I float the notion that he has let go of control of his life and seems happier for it. He shrugs and chuckles. Once his respite stay is up, if he becomes a permanent resident of this assisted living facility, I think he will do so without a fight. I could be wrong, but I doubt it. His surrender and his letting go are a relief for all of us—his family, his friends, and Jim himself. Even if temporary, Jim’s transformation is one more proof to me that miracles happen.